THE MAY DAY STORY

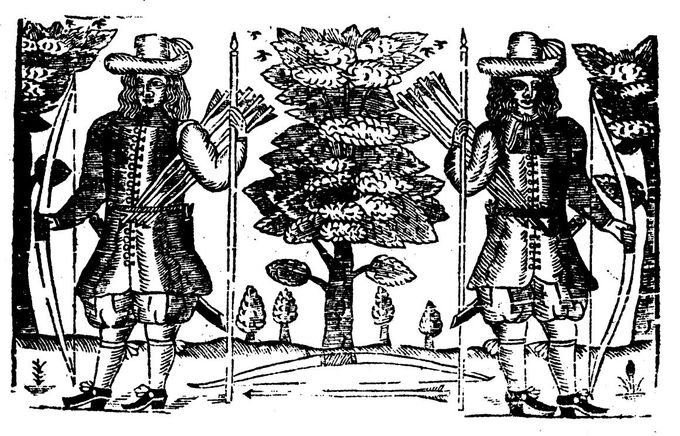

May Day revellers, from RURAL RECREATIONS or, The Young-Men and Maids Merriment at their Dancing round a Country MAY-POLE (17th-century ballad sheet)

Flora from a Roman mural at Pompeii

'Lewd men and light women...'

Some primal instinct to bring garlands and greenery in to the city, to dance and make music, featured in Oxford's Maytime celebrations long before choirs sang the Hymnus Eucharisticus from Magdalen Tower. Indeed, that instinct to welcome the summer with green, carnival gaiety even predates any records of morris dancing.

The Magdalen tradition is only documented from 1695 when the great diarist of Oxford, Anthony Wood, first recorded the ritual as an invocation to the summer: ‘the choral ministers of this House do, according to an ancient custom, salute Flora every year on the first of May, at four in the morning, with vocal music of several parts. Which having been sometimes well performed, hath given great content to the neighbourhood and auditors underneath’.

There is no mention of the Hymnus; nor any suggestion by Wood that church music was sung at all. Rather, May Day was greeted with secular part songs dedicated to Flora, the Roman goddess of flowers.

To 17th-century Puritans, reviving the deity was deeply disquieting. They saw Flora as a living reality, a profane heathen goddess come to life in the May Queen. In May the Romans had honoured her with a festival called the Floralia. The country was reverting to paganism!

Thomas Hall, in his ferocious rant Funebria florae, the downfall of May-games (1660), rails against Flora as a whore ‘of the city of Rome, in the county of Babylon’. Her worship brought in a pack of ‘ignorants, atheists, papists, drunkards, swearers, swash-bucklers, maid-marions, morris dancers, maskers, mummers, may-pole stealers, health-drinkers, gamesters, lewd men and light women’.

It is doubtful whether hymning Flora in Oxford was a custom that descended directly from Roman times. But Flora did appeal greatly to Renaissance humanists who, in their enthusiasm for classical motifs, revived the goddess in both painting and verse.

Their enthusiasm was transmitted to popular tradition. A 17th-century street ballad 'The Dairymaids' Mirth and Pastime on May Day' begins with a literary flourish honouring Flora: 'Now the Season of Winter doth his power resign/ Aye and Flora doth enter in her glory and prime.'

'To salute the great goddess...'

Singing from atop church towers was a widespread custom in Renaissance Europe. Besides Magdalen, New College in the early 17th century had its own May Day celebration. Anthony Wood describes how the singing from New College tower was followed by a procession to St Bartholomew’s Hospital on Cowley Road, with ‘lords and ladies, garlands, fifes, flutes and drums to salute the great goddess Flora and to attribute her all praise with dancing and music.’ The New College ceremony was only abandoned due to clashes with Magdalen men and ‘the rabble of the town’.

So, singing from church towers in Oxford did not originally have the character of a Christian celebration, nor was the custom unique to Magdalen College. Flora – goddess of flowers – was the focus. And history records that garlanded maskers and mummers were already a feature of the May revels in Oxford before the singing began.

Bringing in branches at Maytime, from a Book of Hours by Jean Poyer, 1500

17th-century woodblock from the ballad sheet 'The May Day Country Mirth'

'Dancing in masks, disorderly noises...''

The first of May has been celebrated since ancient times to honour the seasonal rebirth of vegetation. While the Romans had their Floralia, the Celts observed Beltane, and Germanic peoples had their equivalent, known as Walpurgisnacht.

Maytime revels were already controversial in the 13th century, though there is no mention of the Morris as yet. The earliest accounts chiefly refer to the practice of going out into the countryside to gather flowers and greenery and ‘bring in the May’. Branches and blossom were used to decorate homes and public buildings, so welcoming the season.

In 1250, the Chancellor of Oxford University forbade ‘alike in churches, all dancing in masks or with disorderly noises, and all processions of men wearing wreaths and garlands made of leaves of trees or flowers or what not.’

'Men attired in women's apparel...'

Morris dancing was first recorded in England in 1448 when the Worshipful Company of Goldsmiths in London made payments to a harper, a piper and morris dancers to perform at their annual feast. No one knows for sure how it started, but it does seem that the Morris was originally danced as some form of Court entertainment and only later became more widespread as a rural activity, perhaps fusing with local traditions.

By the 16th century May games and morris dancing are closely associated. In Oxford in 1599, we are told:

‘The inhabitants assembled on the two Sundays before Ascension Day, and on that day, with drum and shot and other weapons, and men attired in women’s apparel, brought into the town a woman bedecked with garlands and flowers named by them the Queen of the May. They also had morris dancers and other disordered and unseemly sports, and intended the Sunday to continue the same abuses.’

It is interesting to note the reference to Ascension Day (traditionally celebrated on a Thursday, the fortieth day of Easter). This may fall in May or June, so the revels were not only associated with May Day itself but with more general springtime festivities. In Oxford, beating the parish bounds on Holy Thursday was an age-old custom with which the games were associated. And throughout Britain, they were often celebrated around Whitsuntide, which often falls in June.

The report also alludes to ‘men attired in women’s apparel’. Cross-dressing was a ribald feature of morris celebrations, which particularly scandalised opponents. The Puritan Christopher Fetherston fulminated against the practice in his Dialogue Against Light, Lewd and Lascivious Dancing (1582). ‘For the abuses which are committed in your May games are infinite. The first whereof is this, that you do use to attire men in women’s apparel, whom you do most commonly call May Marrions, whereby you infringe that straight commandment which is given in Deuteronomy 22.5. That men must not put on women’s apparel for fear of enormities.’

Confrontations are recorded. In 1598 there was a May game clash between some youths of the town and the University authorities. The revellers included the mayor’s son, William Furness. In 1617 ‘riding company’ disguised on May Day were held to be in contempt of the Mayor and council. The subversive crew included William Stevenson an apprentice, William Stapler, Frost the cobbler, Peter Short the cutler, Tilcock the painter and Pigeon the chimney sweep. All the riders were put in the stocks for two hours the next market day, with papers on their hats explaining the cause of their punishment.

'This stinking idol...'

Ironically, all the most vivid descriptions of the Maytime frolics are provided by the Puritan pamphleteers who most detested them. Philip Stubbes in his Anatomie of Abuses (1583) paints a wonderfully lurid picture, describing how men and women, young and old, would run out to the woods on May Eve and spend all night making merry. They returned in the morning with birch and branches of trees, in big crowds.

‘Their chiefest jewel they bring home from thence is their Maypole, which they bring home with great veneration, as thus. They have twenty or forty yoke of Oxen every Ox having a sweet nose-gay of flowers placed on the tip of his horns. This Maypole (this stinking idol rather) which is covered all over with flowers and herbs, bound round about with strings, from the top to the bottom, and sometimes painted with variable colours with two or three hundred men, women and children following it with great devotion. And thus being reared up with handkerchiefs and flags streaming on the top they straw the ground about, bind green boughs about it, set up summer houses, bowers and arbours hard by it. And then fall they to banquet and feast, to leap and dance about it, as the Heathen people did at the dedication of their Idols.’

The Maypole seems to have been the focal point for wider festivities, and the ‘summer houses, bowers and arbours’ evoke quite elaborate scenes. The bowers may have been shady retreats in which to chill out; for serving ale; or both. Altogether, accounts irresistibly evoke contemporary preparations for setting up an impromptu rave.

A makeshift 'bower' is shown to the right in this detail from 'St. George's Kermis with the Dance around the Maypole' by Pieter Breughel the Younger, 16th century.

'For setting up Robin Hood's bower...'

But the games were not just spontaneous events. They required some preparation - and funding which might be solicited from local landlords or the parish church. At Thame in 1554, churchwardens’ accounts show that money was paid for buying thirteen yards of green fabric and two-and-a-half of yellow to make coats for the morris men, and to buy them bells. In churchwardens’ accounts for the parish of St Helen’s in Abingdon, 1566, is the following note: ‘Paid for setting up Robin Hood’s bower, eighteenpence.’

Robin Hood and his merry companions were stock figures in morris frolics. How could the church bring itself to finance them? The explanation can be found in the long tradition of church ales, festivals which had been staged since mediaeval times for fund-raising. The church wardens financed the amusements and sold the ale. Profits then paid for the maintenance of the parish church, or were distributed as alms to the poor.

So began a cheery complicity - deep-rooted in many towns and villages - between the parish church and the disorderly revellers. Some parishes even kept their own sets of morris costumes in church to be brought out for their annual Whitsun Ale celebrations.

In fact, it could be said that there was a more general complicity between the morris and the whole 17th-century Establishment. The gentry commonly paid for the village morris to dance at their great houses, as domestic account books show. And the Oxford colleges also hired morris dancers and musicians to perform at their festivities. In the reign of James I a morris was danced before the King himself when he visited Christ Church, as indicated by this entry from the University records: 'x6. Suites for morrice dancers all lyke with garters of bells. For the Playes at the Kinges comminge. 1605.'

Robin Hood - a folk hero celebrated in the May Day revels

The Puritan backlash

The Puritans were horrified by all May customs and their attack on the celebrations in Oxfordshire was led from Banbury, famous as a hotbed of Puritan zealotry. Vicar Thomas Bracebridge fronted the effort to destroy the Banbury Maypoles and all other heathen practices. On 20 May 1589 the constable of Banbury issued an edict to ‘take down all Maypoles within his district and to repress and put down all Whitsun ales, May games and morris dances and utterly to forbid any wakes or fairs to be kept.’

However, John Danvers, Sheriff of Oxfordshire, thought the Puritans too extreme and complained to the Lord Chancellor about the proposed bans. He also ordered the Banbury Justices of the Peace to resist any violent destruction of Maypoles. Legal deadlock was broken when Banbury’s Puritan mob took matters into their own hands by destroying the Maypoles themselves. In response, Vicar Bracebridge’s opponents had him removed from his post.

The duel between May revellers and their adversaries continued into the 17th century. Maypoles and morris dancing were specifically mentioned as ‘harmless recreation’ in King James I's Book of Sports (1618), reissued by Charles I (1633). But with a Puritan spirit abroad, many Anglican churchmen also came to denounce the customs as ungodly, and placed local bans on them. In Oxford, Bishop John Howson twice prohibited the morris in his diocese (1619 and 1622); and Bishop Richard Corbet did so in 1629. For a Puritan attack on a garland ceremony in Oxford click on May Garlands above.

Under Cromwell’s Protectorate the pendulum swung entirely in the Puritan direction; the May revels were shut down everywhere. In Oxford, Anthony Wood reports: ‘1648 May 1. This day the Visitors, Mayor, and the chief officer of the well-affected of the University and City spent in zealous persecuting of the young people that followed May-Games, by breaking of Garlands, taking away fiddles from Musicians, dispersing Morrice-Dancers, and by not suffering a green bough to be worn in a hat or stuck up at any door, esteeming it a superstition or rather an heathenish custom.’

May Day, 1698

'Violent for Maypoles'

The May games returned with the Restoration of 1660 to widespread rejoicing. Anthony Wood reports, ‘This Holy Thursday (31 May) the people of Oxon were so violent for Maypoles in opposition to the Puritans that there was numbered 12 Maypoles besides 3 or 4 morrises.’

But this glorious renaissance was not to last. Wood reports that after 1660 the people of Oxford flagged in their zeal for the May revels, although one or two poles still appeared every year. And the morris faced ongoing opposition. Though Charles II, like his father and grandfather, viewed their frolics as harmless recreations, individual churchmen continued to impose local bans on the morris, including two Bishops of Oxford: Robert Skinner (1662); and Walter Blandford (1666).

The Puritans might be out of power, but their polemics continued unabated. Besides railing against the heathen Flora, Thomas Hall in his 1660 Downfall of May-games complains that most of the Maypoles are stolen. ‘There were two maypoles set up in my parish; the one was stolen and the other was given by a professed papist.’ The charge of complicity between the heathen morris and abhorrent Papacy is a recurrent theme in Puritan attacks. The suggestion of Catholic connivance can be taken as mere propaganda. But truth be told, it does appear that Maypoles were often cut from woodlands without permission. It is also clear that whatever individual bishops might say, the old understanding between parish church and May-revellers lived on. The Establishment remained tolerant - or even supportive - of the games (see Maypoles above).

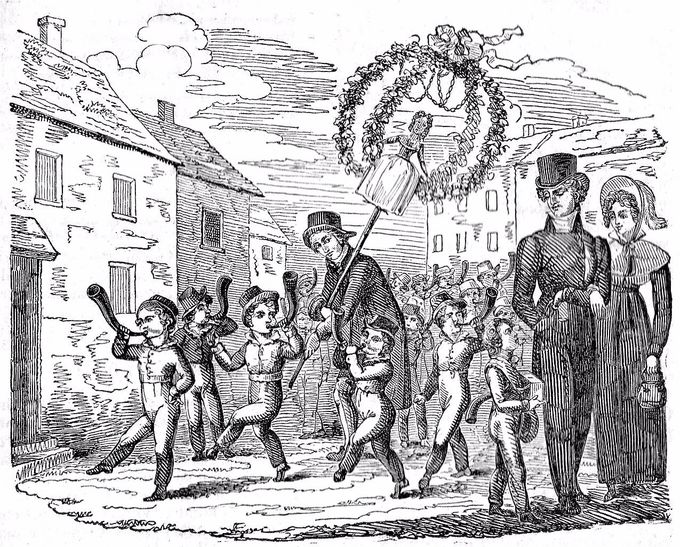

Hornblowers accompany the May garland, from Hone's Table Book of 1827. The setting is Norfolk but it could just as well be Oxford where boys also blew horns on May Morning.

'The boys in the town blow horns...'

Gradually during the 18th century the character of the May revels seems to have changed. We hear less of maypoles in Oxford and more of boys blowing horns. It is reported that boys in Oxford used to blow cows’ horns or hollow canes early on May morning. In 1724, Thomas Hearne writes that the horns were used in Maytime as drinking vessels as well as for making music: ‘The custom of blowing them prevails, at that season, even to this day, at Oxford, to remind people of the pleasantness of that part of the Year, which ought to create Mirth and Gayety.’

Shepilinda’s Memoirs of the City and University of Oxford (1737) describes how, ‘In the City of Oxford there is a custom on May Day for all the boys in town to blow horns, which that they might be perfect in, they begin to blow from the first of April, but of the particular morning they begin by two o’clock. The tradition of this is, that once upon a time the Tradesmen of the City went all out a gathering May in a morning, in which time their wives made them all cuckolds, so to warn all honest Mechanical Husbands to keep from May Frolics, and take care of their Spouses at home.’

Whit-Horns, recently made from willow bark (modelled from the examples in the Pitt Rivers Museum). They play well apparently. Photo by courtesy of Michael Heaney.

Whit-Horns

Among the most curious instruments in the Pitt Rivers Museum are some Whit-Horns fashioned from strips of willow bark wound into a funnel and fixed with hawthorn or blackthorn spines. The reed was made of bark and the mouthpiece pinched around it to create a primitive oboe. In the early 19th century it was traditional for the Oxfordshire villages of Hailey, Crawley and Witney to celebrate Whit Monday with a hunt at Wychwood Forest. The horns were sounded at dawn to wake the village.

Horn-blowing was co-opted into town vs gown rivalry. From about 1800 boys from Oxford were blowing them at the foot of Magdalen Tower to try and drown out the choristers.

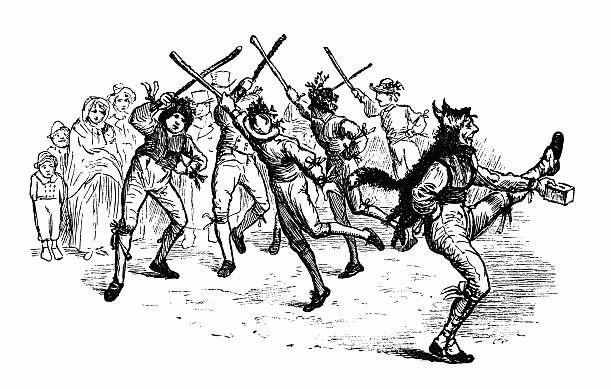

Morris dancers depicted in 1876 by Randolph Caldecott (from Washington Irving's 'Old Christmas'). Though generally declining at this time, the tradition remained vigorous in some English villages.

May Day pageantry at Great Tew, 1911. The children pose outside the parish church which now gives its blessing to the revels.

Merrie England

The morris seem to been active on May Morning in Oxford during the 19th century. The Oxfordshire History Centre possesses a remarkable photograph by Henry W. Taunt of a party on Broad Street, May Day 1886, with the eerie figure of a Jack-in-the-Green as the focus of attention (for more on the Jack see The Morris in Oxford).

It may be that the morris who appeared on the streets of Victorian Oxford came in from Headington and other surrounding villages. We have no evidence of an Oxford side dancing. What is certain is that May Morning in Oxford changed in the latter half of the Victorian age as Magdalen Tower came increasingly into the picture - and Headington spurred a nationwide morris revival.

The long battle between Pagans and Puritans was over. Dancing around Maypoles, morris displays and the election of May Queens - human replicas of the once-abhorred Flora - were all subsumed into the Victorian myth of Merrie England.

Three eminent Victorians helped legitimise May Day: Alfred Tennyson with his long poem The May Queen; Holman Hunt with his iconic painting May Morning on Magdalen Tower; and John Ruskin who ritualised May celebrations at Whitelands College in Chelsea, a training college for women teachers who carried customs into the school curriculum.

For developments see The Morris in Oxford and Magdalen Tower in the MENU above.

For more on Maypoles, The May Queen, May Garlands and The May Tree click on subpages above.

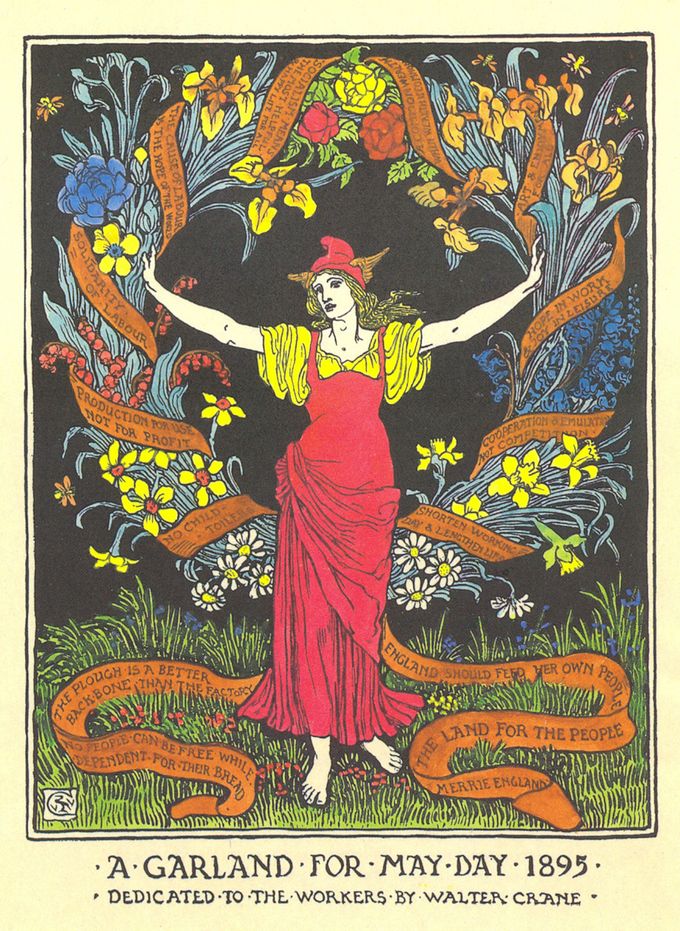

Poster by the artist Walter Crane. In 1890 May Day was celebrated as International Workers' Day, a day of protests in support of an 8-hour working day. It has remained a special day for campaigning in the labour movement.

Share this page